This is an unusual example of relative motion, but it’s very familiar to those “who go down to the sea in ships.” It’s based on the starting leg of one of our Bahamas cruises many years ago.

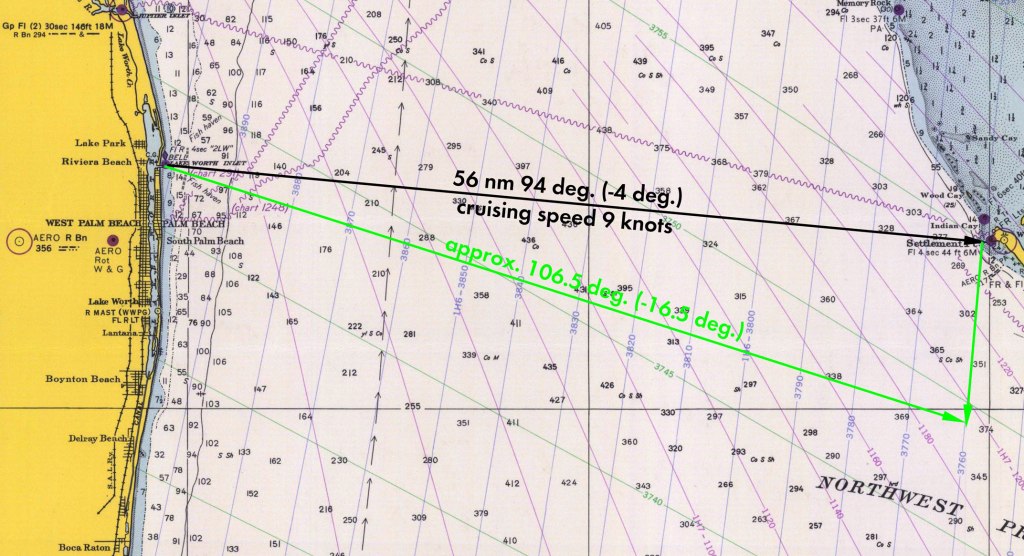

The basic problem can be seen below. The first leg was from Lake Worth Inlet in Florida to West End in the Bahamas. The straight line course can be seen below.

I’ve rounded a few things for simplicity, but it’s pretty accurate. The distance is in nautical miles and the cruising speed is in knots (nautical miles per hour.) The cruising speed was a limitation of our boat; we definitely took the “slow boat to the Bahamas,” especially by current standards. One complicating factor is that navigators and engineers don’t use the same “compass rose.” Navigators set zero degrees north and go clockwise; engineers set zero degrees to the east and go counterclockwise. We’ll state things in both systems.

In any case this looks simple: set the compass for 94 deg., pass the buoy at the inlet and go, right? Wrong. Since this is a relative motion problem, we could expect something else to move. In this case it’s the Gulf Stream, one of the most powerful currents in the ocean. You can see the chain of arrows on the left hand side of the chart, which is the centre of the Gulf Stream. Whether the boat is cruising or at rest, if it’s in the Gulf Stream and unanchored it’s going to be carried along by the Gulf Stream. Let’s assume for simplicity that a) the Gulf Stream drift is uniform across the Straits of Florida and b) it is moving at 2 knots perpendicular to the original course. If we ignore its effects the result will look like this:

The red arrow pointing upward at the right is the vector effect of the Gulf Stream. The red line crossing the Straits of Florida is the course we’d end up with if we just let things “take their course.” With a little more push from the south (or a slower cruising speed) we’d end up on Memory Rock, an event no one on board would forget.

Let’s put some numbers to this: The unit vector for the original course is

(1)

where θ is the angle (engineers’ convention) of the course. The unit vector for the Gulf Stream is

(2)

As discussed in the post Particle Kinematics for Straight Line Motion, the velocity and position vectors for particles in straight line motion are in the same direction, which is why we move between one and the other so easily. In any case a) the velocity vector for the original course is obtained by multiplying Equation (1) by the scalar velocity of the boat and b) the velocity vector for the Gulf Stream is obtained by multiplying Equation (2) by the scalar velocity of the Gulf Stream. Doing this and adding them together yields the velocity vector for the resulting course, or

(3)

Where vb is the cruising speed of the boat and vg is the speed of the Gulf Stream. Substituting θ = – 4 deg., vb = 9 knots and vg = 2 knots yields the following:

(4)

Dividing the coefficient of the j vector by that of the i vector yields the tangent of the angle of the resulting course, which converts to 8.5 degrees, as shown in the diagram.

So how do we deal with this? We start by determining a course–at least to start with–which will set the boat into the Gulf Stream in such a way that, if we keep the rudder straight, we’ll end up at West End. To do this we reverse the Gulf Stream vector as shown below.

If we take the negative unit vector of Equation (2), multiply it by vg, and then adding it as we did in Equation (3), we end up with the corrected velocity of

(5)

Taking the tangent the same way as we did with Equation (4) yields θ = -16.5 degrees, as shown.

But how will this help? If we started from Lake Worth Inlet on this course and told the pilot (or autopilot) to hold the rudder steady at centre, the Gulf Stream will do its work and in theory we would take a curved course and end up at West End. In reality it’s more complicated because the Gulf Stream is not uniform. Today we have computerised navigation which will make the initial course correction (such as shown above) and later course corrections to reach our destination; how we did it at the time is another post.

I have prepared a video which goes over what’s here and more in a general way.

We made it across the Straits of Florida, but how this cruise almost ended in disaster can be found in our post When You Need a Native Guide.