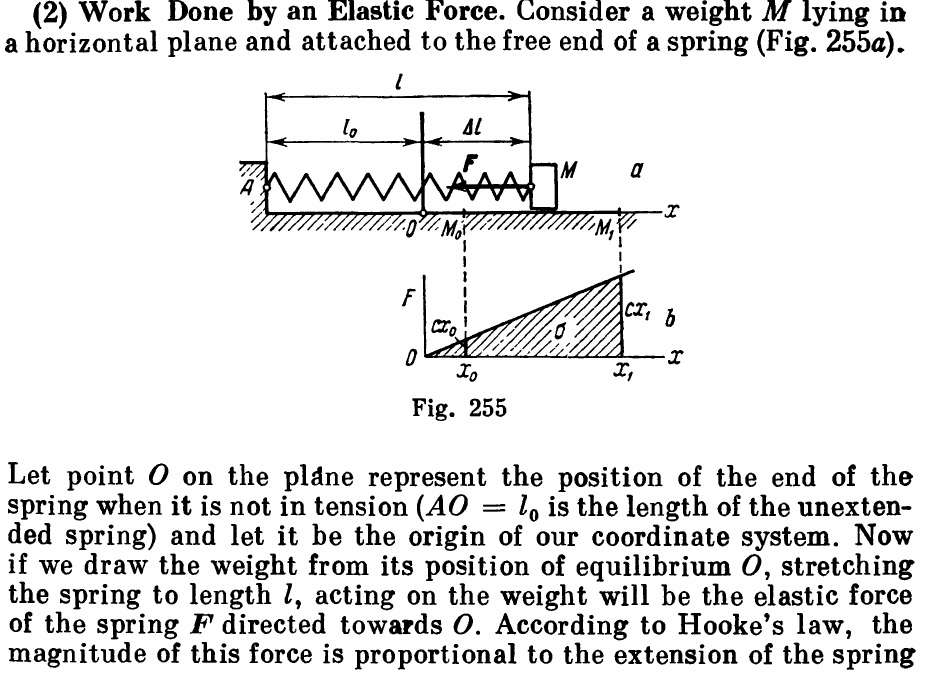

In this post we will look at work and energy in elastic springs. We start with the theory behind them, taken from Theoretical Mechanics – A Short Course -Targ.

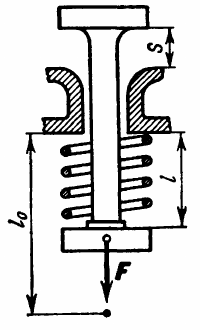

For an example, we turn again to Theoretical Mechanics – A Short Course -Targ. The example is taken from valve springs and valves such as were are used in reciprocating internal combustion engines, which powered both plane and car pictured above with Chet.

The valve is shown in the open position, when s = 6 mm. The uncompressed length of the valve l0 = 60 mm and the compressed length shown is l = 40 mm. The spring constant for the valve spring is 100 N/m and the mass of the valve is 400 g = 0.4 kg. Determine the velocity at the point when the valve closes (s = 0) starting at the situation where the valve is as shown and the valve is at rest.

A general expression of the energy in the valve is

(1)

Where the two values of KE are the kinetic energy at the start (point 1) and at the end (point 2) of the valve movement distance under consideration. Since the valve starts at rest, and

(2)

The energy is the change in energy between the two points. The only force acting on the valve is the spring, which means that, from Equation (40) above,

(3)

where c is the spring constant of the valve (usually k in American usage,) and

are the initial and final compressions of the valve in mm, and

and

are the final and initial velocities of the valve in mm/sec.

We know that . Solving Equation (3) for

,

(4)

The tricky part is in determining the valve length. In the problem statement they are not given directly but through the geometry of the system. As noted, the uncompressed length of the valve is l0 = 60 mm and the final compressed length of the valve is s + l = 46 mm, so so the final compression of the valve is . In like manner the initial compressed length of the valve is

.

Substituting, . All of the lengths have been converted to metres.